POSTMENOPAUSAL BLEEDING and malignancies - ppt download

By A Mystery Man Writer

contents Introduction Geriatrics Essentials DD Urogenital atrophy A COMPLETE GYN HISTORY physical examination Pelvic examination Clinical Investigation of Women with Postmenopausal Vaginal Bleeding Anemia

Presented by: dr. menna Shawkat. Prepared by: Dr. basma gaber azab. Lecturer of geriatric medicine and gerontology.

A COMPLETE GYN HISTORY. physical examination. Pelvic examination. Clinical Investigation of Women with Postmenopausal Vaginal Bleeding. Anemia.

The average woman is postmenopausal for one third of her life. Postmenopausal bleeding: is any bleeding from the genital tract occurring in the postmenopausal period, arising after 12 months of amenorrhoea in a women of menopausal age. Abnormal vaginal bleeding may occur in as many as 20% of women aged 65 years or older. Uterine bleeding is associated with hyperplasia or neoplasia in 22% of postmenopausal women.

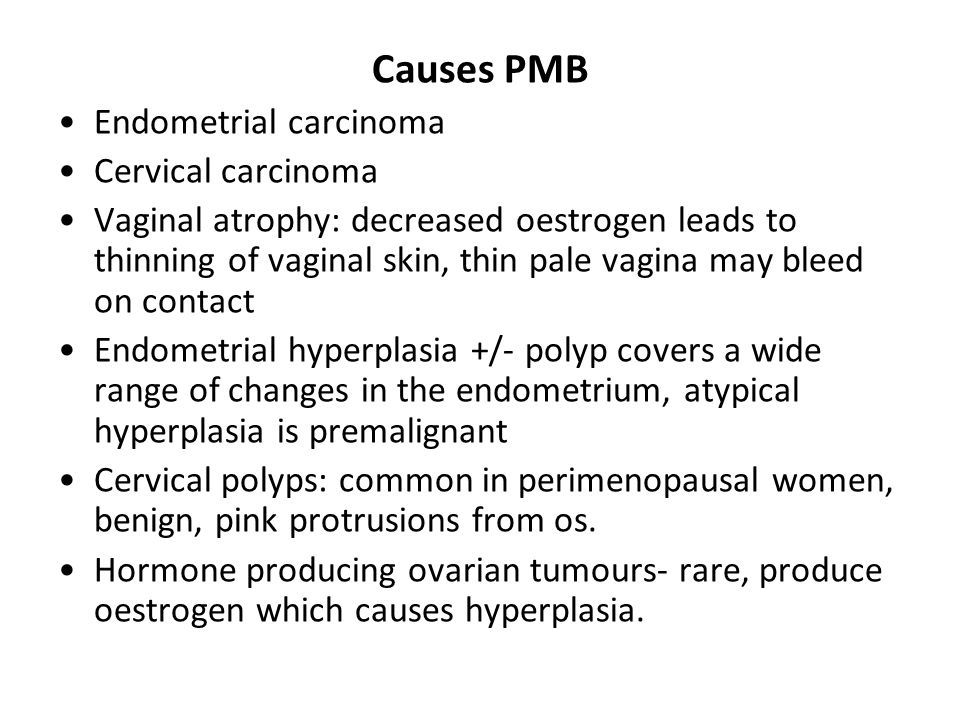

Postmenopausal bleeding is abnormal in most women and requires further evaluation to exclude cancer unless it clearly results from withdrawal of exogenous hormones( hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) use (eg, tamoxifen adjuvant therapy for breast carcinoma). In women not taking exogenous hormones, the most common cause of postmenopausal bleeding is endometrial and vaginal atrophy.

For these patients, a pediatric speculum may be more comfortable..

Evaluate and treat to: Ameliorate benign conditions. Alleviate symptoms. Exclude gynecologic malignancies: any pelvic mass in postmenopausal must exclude malignancy.

Dyspareunia. rugation. Burning. Mucosal thinning. Vaginal bleeding. Inflammation with discharge. vaginal caliber. Urinary urgency and frequency. vaginal depth. pH.

Local estrogen reverses the changes of atrophy with equal effectiveness: Intravaginal cream: 1 gm (¼ - ½ applicator) 2 nights/week. Estrogen ring: 3 months/ring. Intravaginal estradiol tablets: daily for 2 weeks, then 2/week maintenance.

Routine gynecologic issues: Most bleeding is uterine, predominantly from endometrial atrophy. Even if a likely cause is found, other sources must always be ruled out, including hematuria, hematochezia, vulvovaginal pathology, and trauma. Non-gynecologic disorders: Past medical history should identify disorders known to cause bleeding, structural disorders (eg, uterine fibroids, ovarian cysts). Clinicians should identify risk factors for endometrial cancer, including obesity, diabetes, hypertension, prolonged unopposed estrogen use (ie, without progesterone). Easy bruising and excessive bleeding due to toothbrushing, minor lacerations, or venipuncture: A bleeding disorder. Medication history, should include specific questions about hormone use including alternative medicines.

During the general examination, clinicians should look for signs of anemia (eg, conjunctival pallor) and evidence of possible causes of bleeding, including the following: Examination of the patient who presents with vaginal bleeding generally begins with the breast and abdomen, including axillary, supra- and infraclavicular,and inguinal lymph nodes. Hepatomegaly, jaundice, asterixis (flapping tremor of the wrist), or splenomegaly: A liver disorder.

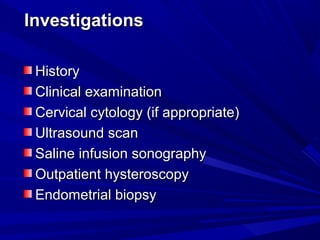

Digital pelvic examination, use left lateral decubitus position if dorsal lithotomy position is uncomfortable. Speculum examination helps identify lesions of the urethra, vagina, and cervix. Bimanual examination is done to evaluate uterine size and pelvic masses , ovarian enlargement.

Assess for urogenital atrophy. Perform Pap smear if indicated. If no blood is present in the vagina, and non-gynecologic : Rectal examination is done to determine neoplasms, hemorrhoids, and induration or nodularity in the posterior cul-de-sac (pouch of Douglas). (eg, perineum, periurethral, perianal) sources.

Evaluation of the Endometrium: Uterine bleeding is associated with hyperplasia or neoplasia in 22% of postmenopausal women, if examination and ultrasonography are inconclusive in women with any of the following: Age > 35. Risk factors for cancer. Endometrial thickening > 4 mm. Office biopsy is the standard endometrial evaluation. Sampling can be done by aspiration or, if the cervical canal requires dilation, by D & C. In postmenopausal women, hysteroscopy with D & C is recommended so that the entire uterine cavity can be assessed only when tissue cannot be adequately sampled or bleeding persists.

A pelvic ultrasound offers additional and separate information, but is not requisite if the biopsy is negative. An ultrasound should be obtained before or several days after the biopsy to avoid artifact. A thin (<5 mm) endometrium on ultrasound usually rules out endometrial neoplasia, but the false-negative rate is up to 4%. Transvaginal Ultrasonography. Outpatient hysteroscopy, sonohysterography, and MRI are other potential screening modalities.

Anemia is a complication of postmenopausal bleeding

Gynecological malignancies

Preoperative assessment. Postoperative care. General considerations about age and treatment of gynecologic malignancies. Palliative care. Types of malignancy.

The USPSTF(US Preventive Services Task Force) recommends against screening for: Breast: mammography/ 2-3 years and breast self examination/month till 74 y. Mammography to age 70 are almost universally recommended ,many organizations recommend till over 70 who have a reasonable life expectancy. Ovarian cancer with transvaginal ultrasonography or CA-125 measurement. Cervical cancer: after 65 with history of normal smears or after 2 normal smears 1 yr apart or who had a hysterectomy for benign disease. Most major health care organizations with the exception of ACOG recommend discontinuation of routine pap smears after age 65 or 70 years if the woman has been appropriately screened in the previous 10 years. Although most guidelines recommend three annual pap smears for previously unscreened women.

Cancers may grow asymptomatically for an extended period, but eventually present with bleeding, discharge, pain, or symptoms involving extension to urinary or rectal structures. Damage or injury to these structures can occur with possible fistula formation. Advanced age is associated with a significantly worse prognosis for endometrial carcinoma patients. It appears that with advancing age, endometrial carcinoma exhibits a more aggressive tumor phenotype, characterized by mutant p53 expression and downregulation of e-cadherin expression, and this, in turn, results in tumors being diagnosed at a more advanced stage in older patients.

Complications of the tumour: torsion, rupture, infection. metastases to pelvic and peri-aortic lymph nodes, as well as over the pelvic and abdominal organs and peritoneum. Complications of treatment: bone marrow depression, infection, neurotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity. Complications of advanced disease: malnutrition, electrolyte imbalance, small and large bowel obstruction, infection, ascites, pleural effusion.

CGA can predict morbidity and mortality in older patients with cancer, and uncover problems relevant to cancer care that would otherwise go unrecognized

Treatment due to age related decline in the functions of the organs and comorbidities. Functional decline and social problems. Individuals with dementia tend to under-report symptoms which leads to delays in medical attention being sought. Thus, they are diagnosed with more advanced stages of cancer, often too late to be treated.

When preoperative risk factors are present, clinicians should be especially vigilant about: Correcting fluid, electrolyte, metabolic derangements. Optimizing replacement of blood loss. Encouraging mobility, avoiding restraints. Maintaining circadian rhythms. Enhancing sensory input. Prescribing medications cautiously.

A syndrome distinct from delirium, characterized by abnormalities in learning and memory. Persists for many months in 10%–30% of patients. No demonstrated link to hypotension, hypoxemia, or type of anesthesia. Treatment is supportive.

Most postsurgical pain requires narcotic analgesia. For cognitively intact patients, consider a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump to improve pain relief and lower use of narcotics.

WHO three-step analgesic ladder. Source: World Health Organization. Technical Report Series No. 804, Figure 2. Geneva: World Health Organization; Reprinted with permission. World Health Organization. Three-Step Analgesic Ladder. Topic.

Patient unable to communicate effectively: Standing orders for narcotic analgesic, with frequent assessment of medication effect. Useful adjuncts: ice packs, heating pads, massage, relaxation techniques. Avoid NSAIDS.

Encourage time out of bed and avoid restraints, to maintain mobility and function. Remove indwelling catheters as soon as possible, to reduce the risk of infection and the effects of restricted mobility. Stop IV fluids, and lift restrictions on diet, as soon as possible. Review medications regularly.

Age alone should not influence the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for the management of cancer. Curative surgery may require more prolonged recovery. Radical surgery, multiagent chemotherapy, and radiation therapy can safely treat gynecologic malignancies in elderly women. Some patients may require treatment modifications due to comorbid conditions.

Chemotherapy doses must be adjusted because age-related changes in renal function include a decrease in the glomerular filtration rate. Drugs excreted primarily via the kidneys must be used with care in the elderly. Dose adjustments for cisplatin (Platinol), ifosfamide (Ifex), methotrexate, and topotecan (Hycamtin) can be based on calculations of creatinine clearance. Some biologic therapies produce less toxicity in older than in younger patients as The development of new delivery systems may reduce drug toxicity significantly. A good example is liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil), which has demonstrated activity similar to that of topotecan in the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer. Cardiac toxicity, alopecia, and mucositis are markedly diminished with liposomal doxorubicin, as compared with the standard formulation of the agent.

Other factors that result in reduced mortality, morbidity, and length of hospital stay are early postoperative mobilization, use of autologous blood transfusions, intraoperative antibiotic prophylaxis, and use of coagulator forceps or hemoclips for improved hemostasis.

For almost 5 decades, RT has been used as an alternative to surgery in poor surgical candidates, mainly patients ≥65, under the assumption that it is less toxic.

Seeks to prevent, relieve, or reduce the symptoms of disease or disorder without effecting cure. Attends closely to emotional, spiritual, and practical needs & goals of patient, family. Usually for those at imminent risk of dying. Also appropriate for those who are extremely ill, living with serious complications, or with advanced chronic disease.

Enhanced cooperation between geriatricians and oncologists may assist the pretreatment assessment of elderly patients and improve treatment guidelines in this population.

Vulvar complaints warrant direct exam. Any chronically irritated area should be biopsied to exclude malignancy.

Squamous hyperplasia. Benign elevated white keratinized lesions. Biopsy should precede treatment. Treatment: Mid-potency corticosteroid twice daily for a few weeks. Lichen sclerosus. Lesions shiny white or pink; parchment-like; can cause shrinkage and adherence of labia minora or extend to perirectal area. Asymptomatic vs. pruritus, vaginal soreness, dyspareunia. Diagnosis confirmed by biopsy. Treatment: Potent corticosteroid for 3 months. Testosterone less effective.

Eczematous pruritus. Triggers include heat, sweating, dryness. Treatment: Identify and eliminate aggravating factors; oral/topical corticosteroids or antihistamines. Lichen planus. Erosive, ulcerative lesions of vulva or vagina resulting in significant discomfort and scarring. Treatment: Mid-potency corticosteroid or daily local estrogen for vaginal involvement.

The incidence of invasive vulvar cancer rises steadily with age, reaching 12 per per year over age 80 years. Pruritus, pain, and a palpable lesion are typical presenting complaints, but particularly frail older women may not be aware of even a large lesion. Many women delay evaluation, leading to a worse prognosis). Any focal, raised, irregular, or pigmented lesion warrants biopsy, which may be performed by the primary care physician without fear of causing spread.

The incidence of vulvar carcinoma in situ increased 400% from 1973 to 2000, predominantly in women younger than 65 years. This parallels the increase in exposure to HPV. By contrast, the incidence of invasive vulvar cancer increased only 20% during this time. While HPV is the most common cause of vulvar carcinoma in situ and invasive vulvar cancer in younger women, only about half of invasive cancers are caused by HPV in women aged older than 65 years. The remainder may be associated with poor Langerhans cell function alone.

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ. This is usually considered a premalignant lesion, although there is some controversy about this. Well-differentiated type has 95% association with vulvar cancer (not HPV) and is seen post-menopause. Identified risk factors include cigarette smoking and HPV exposure. The most common presenting symptom is generalized pruritus of the vulva. It is most often itching that does not go away or get better. An area of VIN may look different than normal vulvar skin. It is often thicker and lighter than the normal skin around it. However, an area of VIN can also appear red, pink, or darker than the surrounding skin.

Some women don t realize that they might have a serious condition. Some try to treat the problem themselves with over-the-counter remedies. Sometimes doctors might not even recognize the condition at first. Multifocal lesions are common, and treatment is often performed with carbon dioxide laser ablation of the lesions. Multiple treatments may be needed and close clinical follow-up is indicated to evaluate for recurrence. The presence of high-grade vin near invasive vulvar carcinomas is usually associated with a poor overall prognosis.

Almost all women with invasive vulvar cancers will have symptoms. These can include: An area on the vulva that looks different from normal – it could be lighter or darker than the normal skin around it, or look red or pink. A bump or lump, which could be red, pink, or white and could have a wart-like or raw surface or feel rough or thick. Thickening of the skin of the vulva. Itching. Pain or burning. Bleeding or discharge. Open sore (especially if it lasts for a month or more) Verrucous carcinoma, a subtype of invasive squamous cell vulvar cancer, appears as cauliflower- like growths similar to genital warts.

A lump. Itching. Pain. Bleeding or discharge. Most vulvar melanomas are black or dark brown, but they can be white, pink, red, or other colors. They can be found throughout the vulva, but most are in the area around the clitoris or on the labia majora or minora. Vulvar melanomas can sometimes start in a mole, so a change in a mole that has been present for years can also indicate melanoma.

Asymmetry: One-half of the mole does not match the other. Border irregularity: The edges of the mole are ragged or notched. Color: The color over the mole is not the same. There may be differing shades of tan, brown, or black and sometimes patches of red, blue, or white. Diameter: The mole is wider than 6 mm (about 1/4 inch). Evolving: The mole is changing in size, shape, or color. The most important sign of melanoma is a change in size, shape, or color of a mole. Still, not all melanomas fit the ABCDE rule. If you have a mole that has changed, ask your doctor to check it out.

Wide local excision may suffice for some early cancers and may be used palliatively in frail women. Radical vulvectomy with inguinal lymphadenectomy, radiation, and chemotherapy may be employed depending on cancer stage and the patient’s overall health status.

A distinct mass (lump) on either side of the opening to the vagina can be the sign of a Bartholin gland carcinoma. More often, however, a lump in this area is from a Bartholin gland cyst, which is much more common (and is not a cancer). Paget disease. Soreness and a red, scaly area are symptoms of Paget disease of the vulva.

Vaginal cancer accounts for only 1% or less of female genital tract cancers. Metastatic disease of the vagina is more common than primary vaginal cancer, notably from cancers of the endometrium, cervix, vulva, ovary, breast, rectum, and kidney. The most common primary vaginal cancer is squamous cell carcinoma, but adenocarcinoma, sarcomas, melanomas, and others do occur. Vaginal squamous cell carcinoma is often preceded by cellular changes and development of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia, which is associated with concomitant cervical or vulvar neoplasia in about 50% of cases. Risk factors for primary vaginal cancer are the same as those for cervical cancer. The incidence is higher in women who have had prior gynecologic cancer, particularly cervical, and those who have undergone radiation therapy.

As many as 20% of vaginal cancers are detected as a result of screening for cervical cancer. Only half are in the upper one-third of the vagina. Inspection of vaginal walls during speculum withdrawal as well as attentive vaginal palpation during the bimanual examination is important. Surgery is the primary treatment for small localized tumors, but radiation is the mainstay of treatment for most vaginal cancers. Radiation therapy is the treatment of choice for most patients with vaginal cancer, and usually requires careful integration of teletherapy and intracavitary or interstitial brachytherapy. External beam and brachytherapy techniques may vary widely, depending on the precise location of the tumor and its relationship to critical structures. Chemotherapy is advocated in some situations.

Treatment of VAIN must be individualized. Numerous treatments, ranging from local surgical excision or ablation through to intracavitary radiotherapy, have been used ,The proximity of the urethra, bladder, and rectum to the vaginal epithelium is an important factor to be considered. Damage or injury to these structures can occur with possible fistula formation, particularly when the patient has had prior pelvic radiation therapy.

Most patients present with painless vaginal bleeding and discharge,and definitive diagnosis can usually be made by biopsy of a gross lesion detected on speculum examination. This can often be done in the office, but may be facilitated by examination under anesthesia. Surgery is the primary treatment for small localized tumors, but radiation is the mainstay of treatment.

Most are deeply invasive and radical surgery has been the mainstay of treatment, often involving some type of pelvic exenteration. Recently, more conservative local excisions have been used, with comparable survival rates reported . This is usually combined with postoperative radiation. Overall 5-year survival is about 10%. Level of Evidence C.

Cervical cancer is the third most common gynecological malignancy diagnosed in the United States. Although it can occur in any age group, the disease is most commonly diagnosed in patients in the fifth and sixth decades of life. The overall incidence of cervical cancer does not differ between women who have undergone prior supracervical hysterectomy (cervix left in situ) and those with an intact uterus.

a history of cervical or vaginal cancer, a history of moderate to severe intraepithelial neoplasia, a weakened immune system, a history of sexually transmitted disease (including HPV), onset of intercourse when younger than 16 years, more than five lifetime sexual partners, exposure to DES in utero. While multiple sexual partners is frequently listed as a risk factor, exposure to one new sexual partner in advanced age is not addressed.

Adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous, and clear cell carcinoma comprise most of the rest. Exposure to HPV, particularly HPV subtypes 16 and 18, is associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer. While HPV is the etiologic agent in most if not all cervical cancers in younger women, an unknown number of cancers in older women are not HPV-related. Nonsquamous cell cancers have higher mortality rates. Having had one normal pap smear reduces the risk of squamous cell more than adenocarcinoma. Studies differ on whether age is associated with worse survival after adjusting for confounders.

Vaginal bleeding, postcoital bleeding, and pain are common presenting symptoms. Early tumors are usually silent and may be diagnosed only by physical examination and pap smear screening. Radial hysterectomy is the primary treatment for patients with cervical cancer in its early stages. In general, surgery is well-tolerated, even in older women, and age has not been identified as a significant risk factor for perioperative complications. Radiation therapy is the primary treatment of locally advanced disease and adjunctive. treatment for many surgically managed cases. Radiation and chemotherapy are also used for palliation in women with metastatic disease, although the overall prognosis is poor.

Is used most often for cancers of the female reproductive organs, including cervical cancer. Staging is based mainly on the results of the doctor s physical exam and a few other tests that are done in some cases, such as cystoscopy and proctoscopy. It is not based on what is found during surgery.

The extent of the main tumor (T) Whether the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N) Whether the cancer has spread (metastasized) to distant parts of the body (M)

Stage 0 (Tis, N0, M0) The cancer cells are only in the cells on the surface of the cervix (the layer of cells lining the cervix), without growing into (invading) deeper tissues of the cervix. This stage is also called carcinoma in situ (CIS) which is part of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN3) Stage I (T1, N0, M0) In this stage the cancer has grown into (invaded) the cervix, but it is not growing outside the uterus (T1). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0). Stage IA (T1a, N0, M0) This is the earliest form of stage I. There is a very small amount of cancer, and it can be seen only under a microscope. The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0).

Stage IA2 (T1a2, N0, M0): The cancer is between 3 mm and 5 mm (about 1/5-inch) deep and less than 7 mm (about 1/4-inch) wide (T1a2). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0). Stage IB (T1b, N0, M0): This includes stage I cancers that can be seen without a microscope as well as cancers that can only be seen with a microscope if they have spread deeper than 5 mm (about 1/5 inch) into connective tissue of the cervix or are wider than 7 mm (T1b). These cancers have not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0). Stage IB1 (T1b1, N0, M0): The cancer can be seen but it is not larger than 4 cm (about 1 3/5 inches) (T1b1). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0). Stage IB2 (T1b2, N0, M0): The cancer can be seen and is larger than 4 cm (T1b2). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0).

Stage IIA (T2a, N0, M0): The cancer has not spread into the tissues next to the cervix (the parametria), but it. may have grown into the upper part of the vagina (T2a). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0). Stage IIA1 (T2a1, N0, M0): The cancer can be seen but it is not larger than 4 cm (about 1 3/5 inches) (T2a1). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0). Stage IIA2 (T2a2, N0, M0): The cancer can be seen and is larger than 4 cm (T2a2). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0). Stage IIB (T2b, N0, M0): The cancer has spread into the tissues next to the cervix (the parametria) (T2b). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0)

Stage IIIA (T3a, N0, M0): The cancer has spread to the lower third of the vagina but not to the walls of the pelvis (T3a). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0). Stage IIIB (T3b, N0, M0; OR T1-T3, N1, M0): The cancer has grown into the walls of the pelvis and/or has blocked one or both ureters causing kidney problems (hydronephrosis) (T3b), OR The cancer has spread to lymph nodes in the pelvis (N1) but not to distant sites (M0). The tumor can be any size and may have spread to the lower part of the vagina or walls of the pelvis (T1 to T3). Stage IV: This is the most advanced stage of cervical cancer. The cancer has spread to nearby organs or other parts of the body. Stage IVA (T4, N0, M0): The cancer has spread to the bladder or rectum, which are organs close to the cervix (T4). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0). Stage IVB (any T, any N, M1): The cancer has spread to distant organs beyond the pelvic area, such as the lungs or liver. (M1)

Endometrial cancers are relatively common, but most myometrial tumors are benign. Endometrial Neoplasia: Endometrial cancer is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy of the female genital tract. Approximately new cases are diagnosed annually in the United States, and it represents the fourth leading cancer among American women. Several risk factors for endometrial cancer have been identified including nulliparity, prolonged exposure to unopposed estrogens, and obesity. These risk factors apply primarily to adenocarcinoma, associated with prolonged unopposed estrogen. The less common serous carcinomas usually arise from atrophic endometrium and tend to be aggressive.

Only 35% to 50% of patients with endometrial cancer will have abnormal findings in pap smear alone. There is no satisfactory technique for routine screening for endometrial cancer. Only 50% of patients with endometrial carcinoma will have abnormalities present in their Pap smear. Annual endometrial sampling is not cost effective for screening asymptomatic women. Likewise, transvaginal ultrasound has not been shown to be cost effective as a screening device because the rate of false-positive results is high. Office endometrial biopsy should be performed. Initial screening pelvic ultrasonography instead of biopsy is acceptable, but the few cases of endometrial cancer arising in a thin endometrium and missed on sonography are usually of the more aggressive serous type. Therefore obtaining a tissue sample is preferable. No guidelines have been established to govern the evaluation of severely impaired women, such as those residing in long-term care. Because limited radiation therapy may palliate symptoms while not causing undue treatment burden, it is wise in most cases to obtain a tissue diagnosis via office biopsy, even if sedation is required.

Radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy are often indicated as adjunctive therapy or in women who are too frail to undergo surgery. The role of laparoscopic surgical techniques is still evolving. It is possible that laparoscopic and robotic technology may eventually lessen the impact of surgical therapy. Prognosis depends on the stage of disease and grade of tumor, with overall 5-year survival estimated at 65%.

Endometrial cancer is staged by examining tissue removed during an operation. This is known as surgical staging, and means that doctors often can’t tell for sure what stage the cancer is until after surgery is done. A doctor may order tests before surgery, such as ultrasound, MRI, or CT scan, to look for signs that a cancer has spread. Although it is not as good as the surgical stage. The 2 systems used for staging endometrial cancer, the FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) system and the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging system are basically the same. The system described below is the most recent AJCC system. It went into effect January The difference between the AJCC system and the FIGO system is that the FIGO system doesn’t include stage 0.

T0: No signs of a tumor in the uterus. Tis: Pre-invasive cancer (also called carcinoma in-situ). Cancer cells are only found in the surface layer of cells of the endometrium, without growing into the layers of cells below. T1: The cancer is only growing in the body of the uterus. It may also be growing into the glands of the cervix, but is not growing into the supporting connective tissue of the cervix. T1a: The cancer is in the endometrium may have grown from the endometrium less than halfway through the underlying muscle layer of the uterus (the myometrium). T1b: The cancer has grown from the endometrium into the myometrium, growing more than halfway through the myometrium. The cancer has not spread beyond the body of the uterus. T2: The cancer has spread from the body of the uterus and is growing into the supporting connective tissue of the cervix (called the cervical stroma). The cancer has not spread outside of the uterus. T3: The cancer has spread outside of the uterus, but has not spread to the inner lining of the rectum or urinary bladder. T3a: The cancer has spread to the outer surface of the uterus (called the serosa) and/or to the fallopian tubes or ovaries (the adnexa) T3b: The cancer has spread to the vagina or to the tissues around the uterus (the parametrium). T4: The cancer has spread to the inner lining of the rectum or urinary bladder. Lymph node spread (N) NX: Spread to nearby lymph nodes cannot be assessed. N0: The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes. N1: The cancer has spread to lymph nodes in the pelvis. N2: The cancer has spread to lymph nodes along the aorta (peri-aortic lymph nodes) Distant spread (M) M0: The cancer has not spread to distant lymph nodes, organs, or tissues. M1: The cancer has spread to distant lymph nodes, the upper abdomen, the omentum, or other organs (such as the lungs or liver)

Information about the tumor, lymph nodes, and any cancer spread is then combined to assign the stage of disease. This process is called stage grouping. The stages are described using the number 0 and Roman numerals from I to IV. Some stages are divided into sub-stages indicated by letters and numbers. Stage 0. Tis, N0, M0: This stage is also known as carcinoma in-situ. Cancer cells are only found in the surface layer of cells of the endometrium, without growing into the layers of cells below. The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes or distant sites. This is a pre-cancerous lesion. This stage is not included in the FIGO staging system. Stage I. T1, N0, M0: The cancer is only growing in the body of the uterus. It may also be growing into the glands of the cervix, but is not growing into the supporting connective tissue of the cervix. The cancer has not spread to lymph nodes or distant sites. Stage IA (T1a, N0, M0): In this earliest form of stage I, the cancer is in the endometrium (inner lining of the uterus) and may have grown from the endometrium less than halfway through the underlying muscle layer of the uterus (the myometrium). It has not spread to lymph nodes or distant sites. Stage IB (T1b, N0, M0): The cancer has grown from the endometrium into the myometrium, growing more than halfway through the myometrium. The cancer has not spread beyond the body of the uterus. Stage II. T2, N0, M0: The cancer has spread from the body of the uterus and is growing into the supporting connective tissue of the cervix (called the cervical stroma). The cancer has not spread outside of the uterus. The cancer has not spread to lymph nodes or distant sites.

Stage IIIA (T3a, N0, M0): The cancer has spread to the outer surface of the uterus (called the serosa) and/or to the fallopian tubes or ovaries (the adnexa). The cancer has not spread to lymph nodes or distant sites. Stage IIIB (T3b, N0, M0): The cancer has spread to the vagina or to the tissues around the uterus (the parametrium). The cancer has not spread to lymph nodes or distant sites. Stage IIIC1 (T1 to T3, N1, M0): The cancer is growing in the body of the uterus. It may have spread to some nearby tissues, but is not growing into the inside of the bladder or rectum. The cancer has spread to pelvic lymph nodes but not to lymph nodes around the aorta or distant sites. Stage IIIC2 (T1 to T3, N2, M0): The cancer is growing in the body of the uterus. It may have spread to some nearby tissues, but is not growing into the inside of the bladder or rectum. The cancer has spread to lymph nodes around the aorta (peri-aortic lymph nodes) but not to distant sites. Stage IV. The cancer has spread to the inner surface of the urinary bladder or the rectum (lower part of the large intestine), to lymph nodes in the groin, and/or to distant organs, such as the bones, omentum or lungs. Stage IVA (T4, any N, M0): The cancer has spread to the inner lining of the rectum or urinary bladder (called the mucosa). It may or may not have spread to nearby lymph nodes but has not spread to distant sites. Stage IVB (any T, any N, M1): The cancer has spread to distant lymph nodes, the upper abdomen, the omentum, or to organs away from the uterus, such as the lungs or bones. The cancer can be any size and it may or may not have spread to lymph nodes.

These can be single or multiple, and can range in size from very small lesions, which do not cause significant symptoms, to large bulky tumors, which can cause abdominal and pelvic pain. Hysterectomy remains the primary form of therapy, but many other techniques are evolving, most notably uterine artery embolization. However, in the absence of hormone therapy, a leiomyoma should not grow and become symptomatic, so any such enlargement is suspicious for cancer. Malignant lesions of the myometrium include leiomyosarcoma and other sarcomatoid tumors. These do not typically cause bleeding in early stages, and may only be detected by the presence of an enlarging uterus or pelvic mass. They are typically aggressive tumors with high metastatic potential. Surgery is usually indicated and adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation may be utilized. Extension of tumor beyond the confines of the uterus is associated with a very poor prognosis.

Its peak incidence occurs between the ages of 50 and 70 years. Specific risk factors include nulliparity, prolonged exposure to estrogen, and mutation of the BRCA-I and BRCA-II genes. Ovarian neoplasms may grow to a considerable size asymptomatically. Because ovarian cancer begins silently, the diagnosis is most commonly made at stage III or stage IV disease. Early diagnosis is difficult because of lack of symptoms and the difficulty of detecting small adnexal masses on pelvic examination. The 5-year survival rate for stage IV disease is less than 20%

It may cause abnormal uterine bleeding. Often associated with ascites. One third of patients with ascites also have a pleural effusion. Ovarian cancers metastasise to pelvic and peri-aortic lymph nodes, as well as over the pelvic and abdominal peritoneum. bloating, gastrointestinal complaints, or a palpable mass, and are usually associated with advanced disease. Atypical presentation: urinary frequency or dyspepsia. Constitutional symptoms include fatigue, weight loss, anorexia and depression. symptoms and signs of complication. In retrospect, most ovarian cancer patients have had symptoms for several months before their cancer is diagnosed. Therefore, ordering a pelvic ultrasound to investigate vague lower abdominal complaints is reasonable. Current screening tests of asymptomatic women, pelvic ultrasonography and serum tumor markers, have a low overall yield and are of limited value except in high-risk patients.

2013 Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidelines advise that women with a family history that appears to increase their risk of developing ovarian cancer should be referred to a clinical genetics service for full assessment of risk.

The woman is a known carrier of BRCA1, BRCA2, or any other known relevant cancer gene mutations. She has a first-degree or second-degree relative who carries a known relevant gene mutation. Two family members who are first-degree relatives of each other have ovarian cancer. A family member who has ovarian cancer at any age and is a first-degree relative of someone who developed breast cancer under the age of 50 years, or of two who developed it under the age of 60 years. Three or more family members with colon cancer; or two with colon cancer and one with stomach, ovarian, endometrial, small bowel or urinary tract cancer in two generations. (One must be diagnosed under the age of 50 years and they should be first-degree relatives of each other.) One family member with both breast and ovarian cancer. These high-risk women should be offered genetic screening and counselling. They may be offered referral for prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy. Women diagnosed with ovarian cancer should be offered genetic screening for the relevant gene mutations.

In fact, the majority of elderly patients are able to tolerate the standard of care for ovarian cancer including initial surgical cytoreduction followed by platinum and taxane chemotherapy. Because functional status has not demonstrated a reliable correlation with either tumor stage or comorbidity, each patient’s comorbidities should be assessed independently. For elderly patients with significant medical comorbidity, the extent of surgery and aggressiveness of chemotherapy should be tailored to the extent of disease, symptoms, overall health, and life goals.

Primary cancers of the fallopian tube are rare. The two most common histologic types include serous and endometrioid tumors. Other types of mullerian carcinomas are less common. Mutations of the BRCA-I and BRCA-II genes may be associated with an increased risk for fallopian tube malignancies. Infections including nontuberculous salpingitis may mimic symptoms of fallopian tube malignancy. The symptoms are similar to those seen with ovarian cancers and include abdominal pain and distension. Diagnosis can be difficult and is often delayed because symptoms may be vague and often do not present until the disease has progressed outside the fallopian tube. These are often aggressive tumors with a poor overall prognosis.

An Inflection Point in Cancer Protein Biomarkers: What was and What's Next - ScienceDirect

Post Menopausal Bleeding - ppt download

Menopause PPT Assessment, PDF, Menopause

The virology, epidemiology, transmission, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, management, and prevention strategies associated with monkeypox

Postmenopausal bleeding for undergraduate

PPT - Endometrial Biopsy PowerPoint Presentation, free download - ID:217129

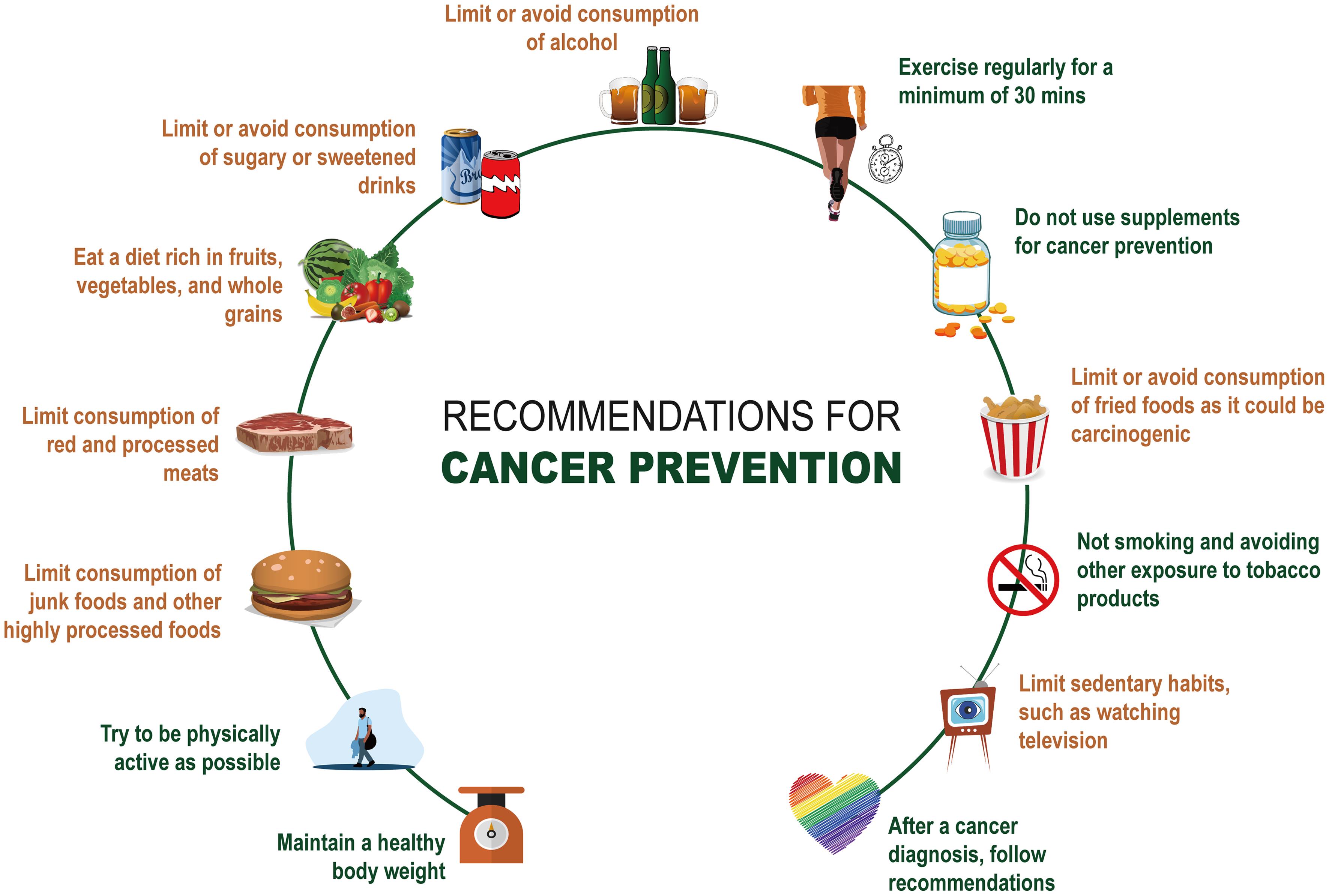

Diet and Supplements in Cancer Prevention

Gynecology PPT Presentation Template - EaTemp

The Essential Guide to Menopause and Inflammation

- JRB Medical Centre - Postmenopausal bleeding is not normal and 90

- PDF] Radiological reasoning: algorithmic workup of abnormal vaginal bleeding with endovaginal sonography and sonohysterography.

- Case Presentation - Post Menopausal Bleeding - MD/DNB Obstetrics & Gynaecology

- Abnormal Uterine Bleeding: The Role of Ultrasound

- Menopause is the end of menstruation. Vaginal bleeding after

- Women's Athletic Pants Lightweight Stretch Casual Pants Running Gym Wo – MAGCOMSEN

- Patachou Girls Chiffon Flowers and Butterflies Dress

- Best Winter Camping Blankets - TMBtent

- ENVY BODY SHOP Silicone Breast Forms M(600g) Size 34C

- Olga Cushioned Women 2 Piece St Bras Set Size 40DD. White & Black Polka Dots